Perioperative and regional anesthesia management for patients on anticoagulation can pose a major problem. Typically, anticoagulants, i.e. blood thinners, are prescribed for patients who are at risk for clotting or thromboses. Common indications for this medication include atrial fibrillation, deep venous thromboses, and mechanical heart valves1. When stopping anticoagulation abruptly, such as for a surgery, rebound hypercoagulability can occur. Meanwhile, keeping a patient on anticoagulation during surgery or neuraxial anesthesia increases the risk of bleeding and hematoma formation. As a result, there are special considerations needed when administering anesthesia to patients on blood thinners.

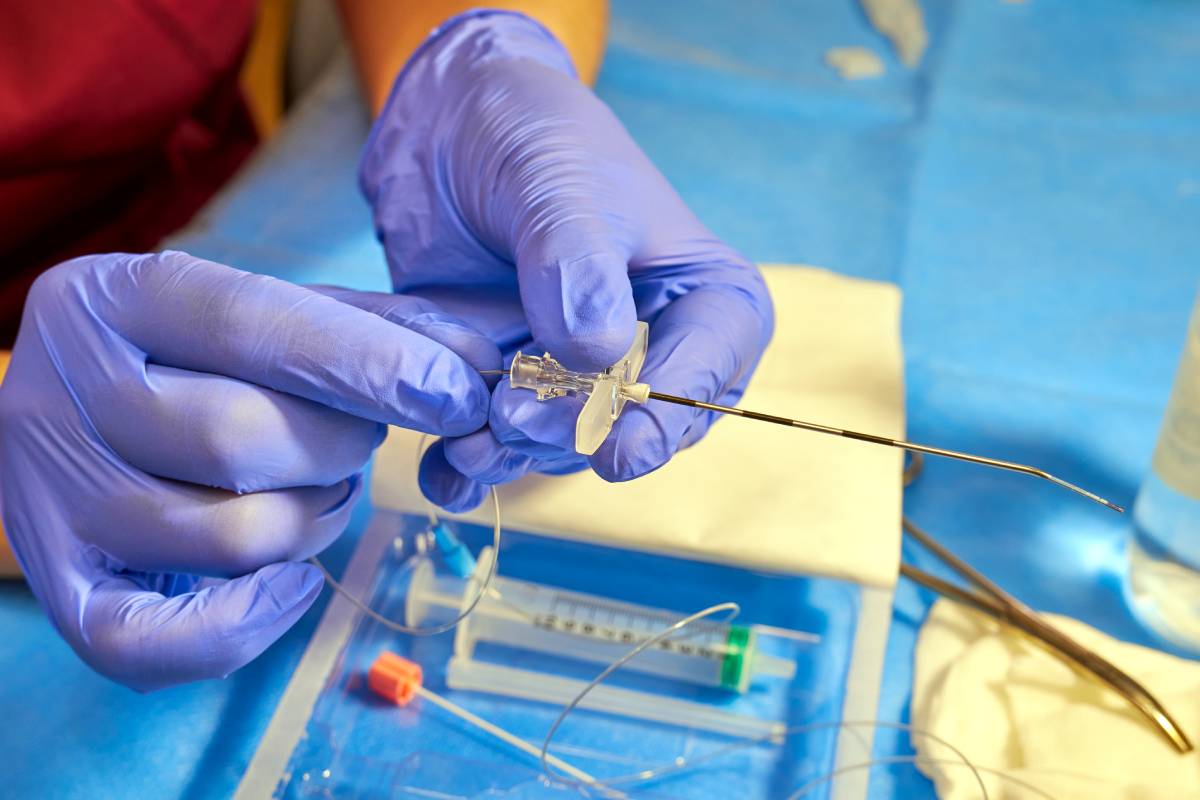

One area of anesthesia where these considerations about bleeding risk on blood thinners are especially important is epidurals placed in the spinal cord. Bleeding risk increases with age, presence of a coagulopathy, abnormalities of the spinal cord, or a prolonged indwelling neuraxial catheter while on anticoagulation2. Interestingly, the anesthesia management of patients differs depending on what anticoagulant a patient is taking2. This is due to the differing pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of each anticoagulant class. Further, patient and surgery specific factors must be taken into account when managing an anticoagulant with anesthesia.

The American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (ASRA) has summarized practice guidelines and recommendations regarding management of anticoagulant agents for regional anesthesia. This can apply to neuraxial blockades and the removal of catheters including epidurals to reduce risk of hematomas3. However, for patients prior to surgery, the evaluation is different. Bleeding risk is assessed with the HAS-BLED score which represents hypertension, abnormal liver or kidney function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile International Normalized Ratio [INR], elderly, drugs and alcohol. Each variable is one point, and a score greater than three indicates a high bleeding risk4. The HAS-BLED score has been found to be a reliable predictor for perioperative bleeding risk and can be used as a guideline for stratifying patients into low and high risk5.

For patients with recent venous thromboembolism (VTE) or an ischemic stroke, the risk of recurrence or a major cardiovascular event is high. Thus, for these patients, recommendations are to defer surgery up to 3 months for those with a VTE and 9 months for those with a recent ischemic stroke6. Further, for patients at particularly high risk for thromboembolism, bridging therapy may be required according to traditional recommendations. This involves replacing a long-acting anticoagulant, such warfarin, with a short-acting one, such as low-molecular weight heparin, prior to surgery. Of note, current data has disputed the efficacy of bridging therapy and thus its use remains in question4.

Overall, while there are guidelines in place from the ASRA for regional anesthesia, perioperative management of anticoagulation requires a different approach. Along with using valid scores like HAS-BLED, using clinical judgement while considering patient factors and the timing of surgery is important. Both for regional anesthesia and perioperatively, balancing risks and benefits in patients is key. With the development of new oral anticoagulation agents and the decreased need for monitoring, such as with apixaban and dabigatran, considerations for anesthesia for patients on blood thinners may be able to be simplified and streamlined to optimize benefits of surgery while minimizing patient risk of either bleeding or thromboses.

References

1. Shaikh SI, Kumari RV, Hegade G et al. Perioperative Considerations and Management of Patients Receiving Anticoagulants. Anesth Essays Res 2017; 11 (1): 10-16.

2. Horlocker TT. Regional anaesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic and antiplatelet therapy. Br J Anaesth 2011; 107 Suppl 1: i96-106.

3. Gogarten W, Vandermeulen E, Van Aken H et al. Regional anaesthesia and antithrombotic agents: recommendations of the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2010; 27 (12): 999-1015.

4. Polania Gutierrez JJ RK. Perioperative Anticoagulation Management. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2021.

5. Omran H, Bauersachs R, Rubenacker S et al. The HAS-BLED score predicts bleedings during bridging of chronic oral anticoagulation. Results from the national multicentre BNK Online bRiDging REgistRy (BORDER). Thromb Haemost 2012; 108 (1): 65-73.

6. Hornor MA, Duane TM, Ehlers AP et al. American College of Surgeons’ Guidelines for the Perioperative Management of Antithrombotic Medication. J Am Coll Surg 2018; 227 (5): 521-536 e521.