Anesthesiology Residency Rotations: A Comprehensive Overview

Anesthesiology residency programs are meticulously structured to provide residents with a broad and in-depth clinical experience. The training typically spans four years: it begins with a Clinical Base Year (PGY-1) and is followed by three years of Clinical Anesthesia (CA-1 to CA-3). Each phase is designed to build upon the previous, ensuring a progressive acquisition of knowledge and skills necessary for competent anesthetic practice. During anesthesiology residency, anesthesiologists-in-training gain experience in diverse clinical settings through rotations and extensive hands-on practice that aim to prepare them for independent practice.

Anesthesiology residency programs are primarily dedicated to cultivating compassionate, knowledgeable, and highly skilled anesthesiologists who can safely and effectively care for patients across a wide range of clinical settings. The mission is to provide comprehensive, progressive training that emphasizes excellence in perioperative medicine, pain management, and critical care 1,2.

The PGY-1 year serves as the foundation for anesthesiology training, emphasizing the development of general medical knowledge and patient care skills. PGY-1 rotations intersect with various specialties, including internal medicine, surgery, emergency medicine, and critical care, to provide a comprehensive understanding of patient management across various medical disciplines at the start of residency 3,4.

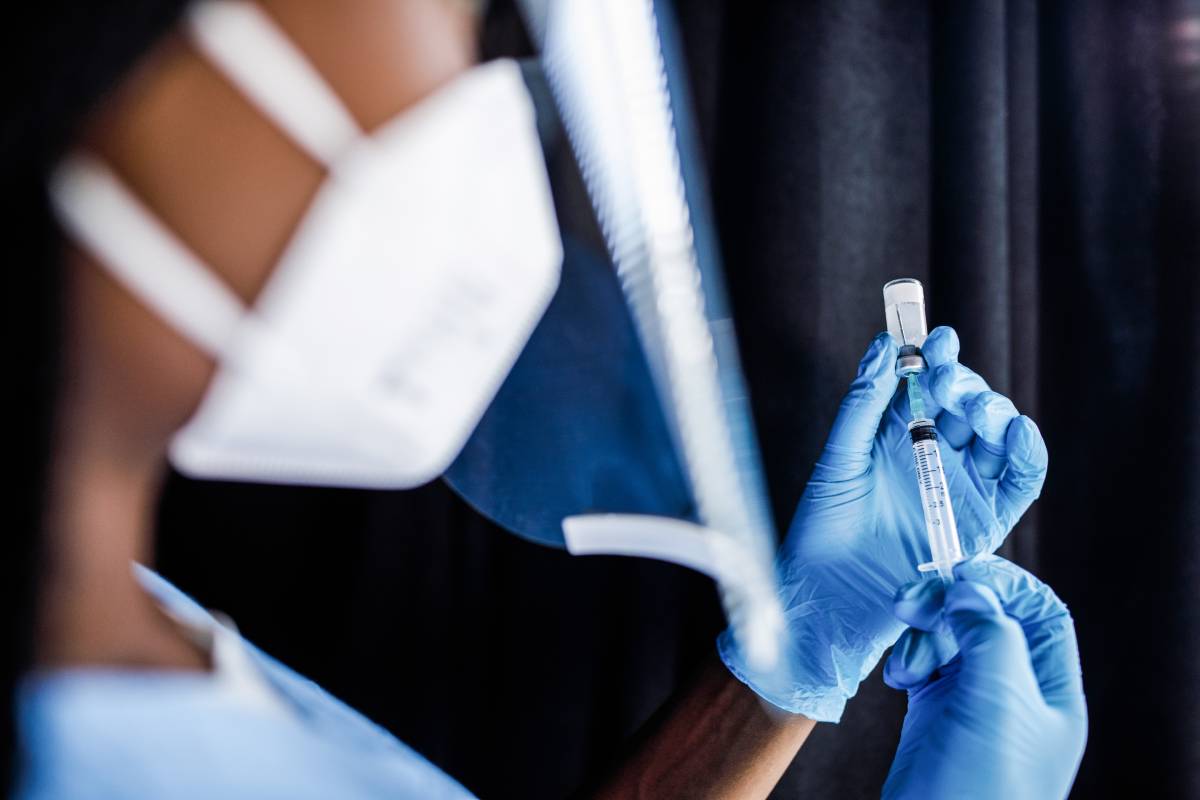

The CA-1 year marks residents’ immersion into the field of anesthesiology. During this period, residents focus on mastering basic anesthetic techniques and perioperative patient management. This year is pivotal in developing the residents’ proficiency in administering anesthesia and managing patients in the perioperative setting 5,6.

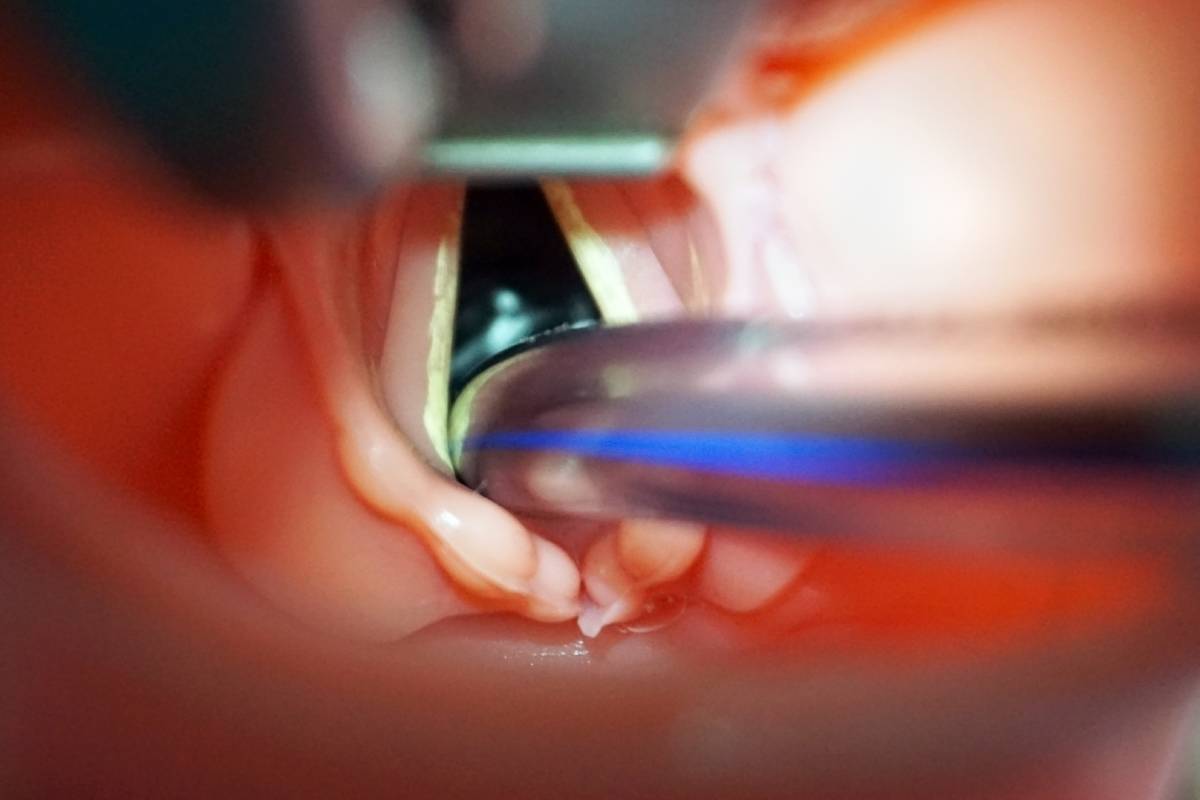

In the CA-2 year, residents delve into anesthesiology subspecialties, gaining exposure to complex surgical cases and advanced anesthetic techniques. Rotations during anesthesiology residency typically include pediatric anesthesia, obstetric anesthesia, cardiothoracic anesthesia, neuroanesthesia, regional anesthesia, and critical care. This diverse clinical exposure equips residents with the skills necessary to manage a wide array of anesthetic challenges 7,8.

The final year of residency, CA-3, focuses on refining clinical skills, fostering leadership abilities, and preparing residents for independent practice. Residents often have the opportunity to tailor their rotations based on career interests, engaging in advanced subspecialty rotations, elective experiences, or in-depth research projects. This flexibility allows residents to align their training with future career goals and interests 9,10.

Anesthesiology residency rotations are thoughtfully designed to provide a comprehensive and progressive training experience. From establishing foundational medical knowledge in the PGY-1 year to refining advanced clinical skills and leadership in the CA-3 year, each phase plays a crucial role in developing competent and confident anesthesiologists. The structured yet flexible nature of these programs ensures that residents are well prepared to meet the diverse challenges of anesthetic practice and to contribute meaningfully to patient care and the broader medical community.

References

1. Miller, J. Mission & Vision – Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine. https://www.uab.edu/medicine/anesthesiology/about/mission-vision.

2. Program Mission & Aims » Department of Anesthesiology » College of Medicine » University of Florida. https://anest.ufl.edu/education/residency/program-aims/.

3. Staszak, J. et al. Changing of an anesthesiology clinical base year to create an integrated 48-month curriculum: experience of one program. J Clin Anesth 17, 225–228 (2005). DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2004.08.005

4. Clinical Base Year (PGY-1). Anesthesiology https://www.anesthesiology.cuimc.columbia.edu/education/residency/clinical-anesthesia-rotations/clinical-base-year-pgy-1 (2017).

5. Curriculum | Anesthesia Residency | IU School of Medicine. https://medicine.iu.edu/anesthesia/education/residency/curriculum.

6. Residency Curriculum Overview. https://medicine.yale.edu/anesthesiology/education/resident-life/curriculum/.

7. Program Structure & Rotations – UW Anesthesiology & Pain Medicine. https://anesthesiology.uw.edu/education/residency-program/program-structure-rotations/.

8. Rotations. Dept. of Anesthesiology | GW School of Medicine and Health Sciences https://anesthesiology.smhs.gwu.edu/rotations.

9. Keck School of Medicine of USC Anesthesiology Residency Program. Department of Anesthesiology https://keck.usc.edu/anesthesiology/training-education/keck-school-of-medicine-residency-program/.

10. Curriculum Anesthesiology Residency | Icahn School of Medicine. Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai https://icahn.mssm.edu/education/residencies-fellowships/list/msh-anesthesiology-residency/curriculum.